Yesterday’s decision, Milne Estate (Re), 2019 ONSC 79, which was an appeal from the Superior Court to the Divisional Court, provided much needed clarity on the question as to whether a will is a trust, whether a will must satisfy the three certainties test, and the investigative role of the court during a probate application. Also, Allocation Clauses (or basket clauses), which were under fire for potentially invalidating a will, were deemed to be acceptable. This blog will look at Justice Dunphy’s decision in Re Milne in the Superior Court, then Justice Penny’s decision in Re Panda and finally, Justice Marrocco’s decision in Re Milne in the Divisional Court.

Why two wills?

Preparing more than one will is a general practice adopted by many will drafting solicitors.

In order to appreciate this dilemma, it is important to understand the meaning of probate, estate administration tax and the benefit of using an Allocation Clause (also known as a basket clause).

Probate is basically a formal approval process where the Court validates a will and confirms the appointment of an the estate trustee. If the probate application is successful, the court issues a Certificate of Appointment of Estate Trustee, which gives the executor legal authority to deal with the estate.

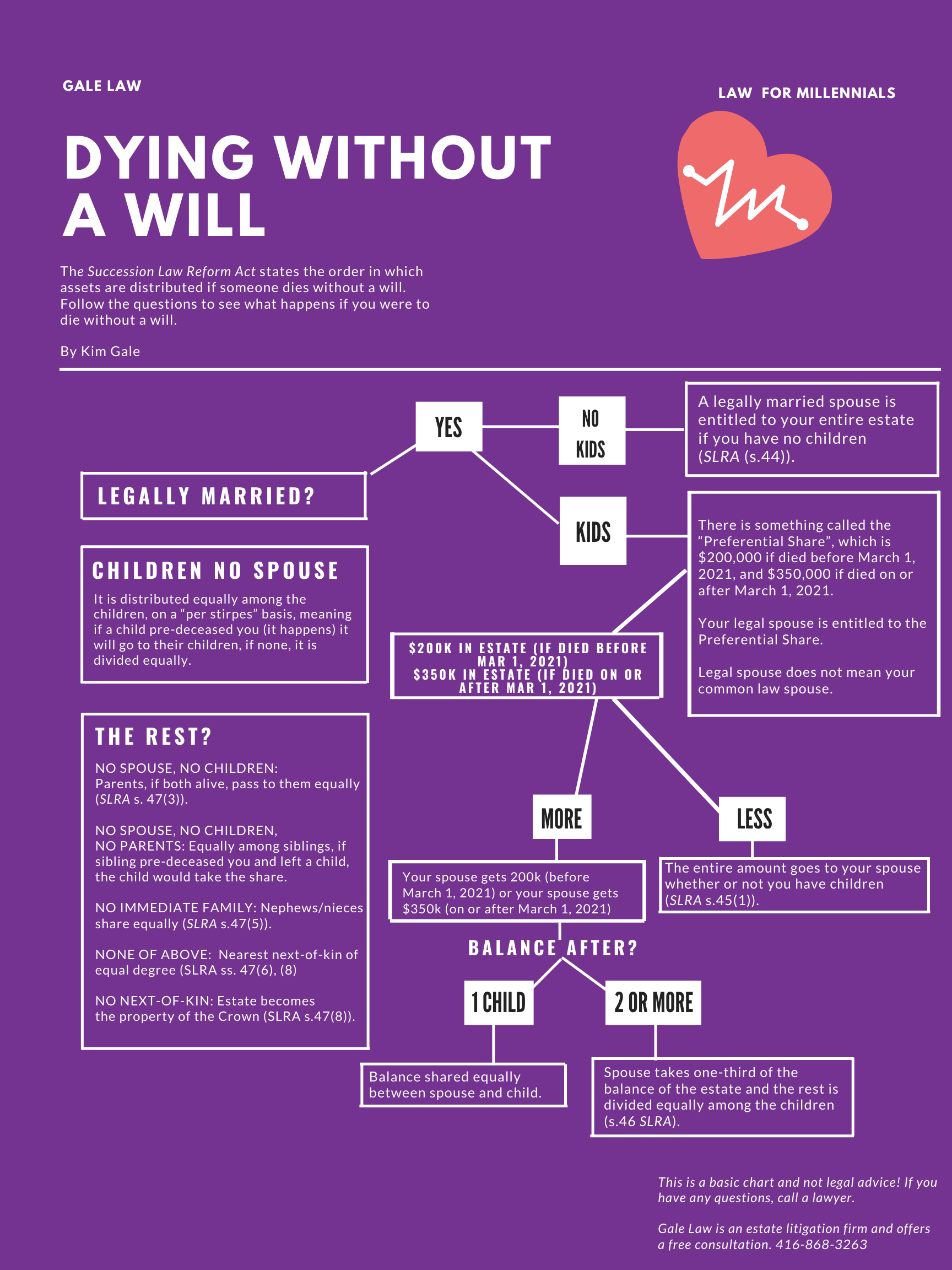

Estate Administration Tax (also known as a probate fee) is a tax imposed on the estate of the deceased person. The rates are:

$5 per $1,000 of estate assets up to $50,000, and.

$15 per $1,000 of estate assets over $50,000.

What is an Allocation Clause?

Probate is not mandatory and not all assets need to be submitted for probate. That is where the Allocation Clause comes in handy and allows the estate trustee discretionary power to determine which estate assets should be probated and which one should not.

An Allocation Clause uses language that is all encompassing. It states that the primary will includes “all assets that require a probated will.” The secondary will includes “all of the assets that do not require probate will.” Assets in the “Primary Will” will be submitted for probate and assets in the “Secondary Will” will not be submitted. The Allocation Clause allows the estate trustee to determine which assets fall under the Primary and Secondary Will.

Even though it is a common practice to include Allocation Clauses, it was uncertain whether using this clause in a will was a “safe” practice or not – until now.

Re Milne in the Superior Court

On September 11, 2018, Justice Dunphy ruled in Milne Estate (Re), 2018 ONSC 4174 that the Primary wills that used the Allocation Clause were invalid.

His honours reasoning was simple: A will is a trust. Therefore, there the “three certainties” applied. These are certainty of intention, subject-matter, and objects. He also stated that is was proper for the court to examine these elements at the stage of probate because the probate function of the court has an inquisitorial function.

Justice Dunphy considered the Secondary Wills to be valid but held that the Primary Wills were invalid “as they failed to describe with certainty any property that is subject to them” (para 28).

This ruling created a sense of insecurity (or panic) in the mind of testators and litigants in respect of the validity of their wills.

Re Panda

On November 13, 2018, Justice Penny’s endorsement respectfully disagreed with Justice Dunphy’s decision in Re Milne Estate and granted probate for a Primary Will that used an Allocation Clause.

The same issue arose before Justice Penny in Re Panda, 2018 ONSC 6734. A motion for directions was brought before Justice Penny where probate was sought for a Primary Will where the Secondary Will had an Allocation Clause which was substantially similar to the one in Re Milne. When the application for Certificate of Appointment of Estate Trustee of the Primary Will came before Justice Dunphy, he refused to grant probate.

Justice Penny held that firstly, the inquisitorial role of the court is limited to whether the document is in fact a will, whether it meets the formal requirements of the Succession Law Reform Act (SLRA) and whether its testamentary in nature. Beyond that, such as broader interpretation questions, should not be addressed on probate applications.

Secondly, Justice Penny ruled that a will is not a trust, therefore, the three certainties test cannot be applied to wills. A will is a different testament then a trust. It is unique in itself. Though it has some features of trust and some of contract, it is neither a trust nor a contract. As Justice Penny stated, “a will is its own, unique creature of law.”

Lastly, in determining whether a testator can confer the ability of his representatives to seek probate of assets as per their discretion, Justice Penny was of the view that this is an issue of construction of a given instruction in the will. This issue was not before him in the Application, however, he stated that a resolution should occur in a case where the issue was raised “in the context of a mature dispute.”

Re Milne Appeal to the Divisional Court

In yesterday’s released decision dated January 24, 2019, Justice Marrocco of the Divisional Court ruled, with Justice Swinton and Justice Sachs consenting, that the appeal was allowed and set aside the order of Justice Dunphy. The Primary Will was deemed valid and there were no costs ordered (as none were sought).

Allocation Clauses: Common Technique

The court acknowledged that Primary and Secondary Wills are a commonly used technique as confirmed by Justice Greer in Granovsky Estate v Ontario (1998) 156 D.L.R (4th) 557. Additionally, Allocation Clauses are a common estate planning technique and the fact that they remain discretionary does not mean that the power is arbitrary. An estate trustee must act as a fiduciary.

Re Panda

Justice Marrocco agreed with Justice Penny’s reasons and conclusions in Re Panda. Kindly see above that decision.

A will is not a trust

Justice Marrocco stated that Justice Dunphy cited no authority for his decision that a will is a trust. He agreed with Justice Penny and stated that “a will may contain a trust, but this is not a requirement for a valid will” (para 35).

However, the plot thickens, as Justice Marrocco referenced section 2(1) of the Estates Administration Act which “vests all real and personal property of a person who has died in the deceased’s personal property” (para 39). Justice Marrocco points out that even if section 2(1) creates a trust, the trust is created by statute and not by the will and would not be subject to the “three certainties” test.

If the three certainties apply the subject-matter of the primary will is certain

Justice Marrocco covers all his bases by saying that even if he is wrong, and a will is a trust, and the three certainties are required, the Primary Wills subject-matter is still certain.

The definition concerning subject-matter of a trust is that it must have property that is clearly defined. Justice Marrocco states that the property in the Primary Wills is clearly identified due to the “objective basis to ascertain it; namely whether a grant of authority by a court…is required…for transfer…of the property. As a result, the Executors can allocate all of the deceased person’s property between the Primary and Secondary Wills on an objective basis” (para 49).

Simply put, the executors are instructed to ascertain if probate is required to transfer an asset, and categorize the asset based on the “objective criterion” (para 50). If the executors make a mistake allocating a property, this error does not disrupt the subject-matter of the trust.

As a result, Justice Marrocco ruled the subject-matter of the Primary Will is certain.

The scope of Probate Review

Justice Marrocco cited Justice Penny’s view: “Broader questions of interpretation and the validity of powers of appointment or other discretionary decision-making conferred on estate trustees are matters of construction and not necessary to the grant of probate.” His honour was inclined to agree with Justice Penny’s reasoning and stated that “Justice Dunphy exceeded his jurisdiction, such a conclusion is not necessary to decide this appeal” (para 53).

Some Clarity?

Finally, estate planners and litigators have some clarity with the use of Allocation Clauses! Allocation Clauses do not invalidate a will. A will is not trust – but even if it a trust – you don’t have to worry about the three certainties.

Our concern is whether this “will is not a trust, but even it is” conundrum may allow further holes to be poked during probate or will challenge applications. This is yet to be seen, but you can sleep well tonight knowing that Allocation Clauses are in the courts good books.

It is worth noting that this appeal was an effort of many parties and we would like to congratulate the Toronto Lawyers Association, Archie Rabinowitz, David Lobl, Brian Cohen, Ian Hull, Timothy Youdan and Stuart Clark!