It is imperative to understand the limitation period to bring a claim in Estate Litigation. If a claim is statute barred (past the limitation period), then the claim will first need to overcome the issue of being out of time, and if the court opines that the claim is statute-barred, then that is the end of the claim (even if it is a meritorious claim).

It is for this reason that it is crucial to understand the limitation period that may apply to different claims and to decipher when the time for limitation starts running.

Limitations Act, 2022

The Limitations Act, 2022 S.O. 2002, c. 24, Sched. B (“Act”), which came into force on January 1, 2004, consolidates, combines and reforms all the provincial laws on limitations. The Act also impacts estate-related statutes such as the Estates Act, Estates Administration Act, Family Law Act, etc.

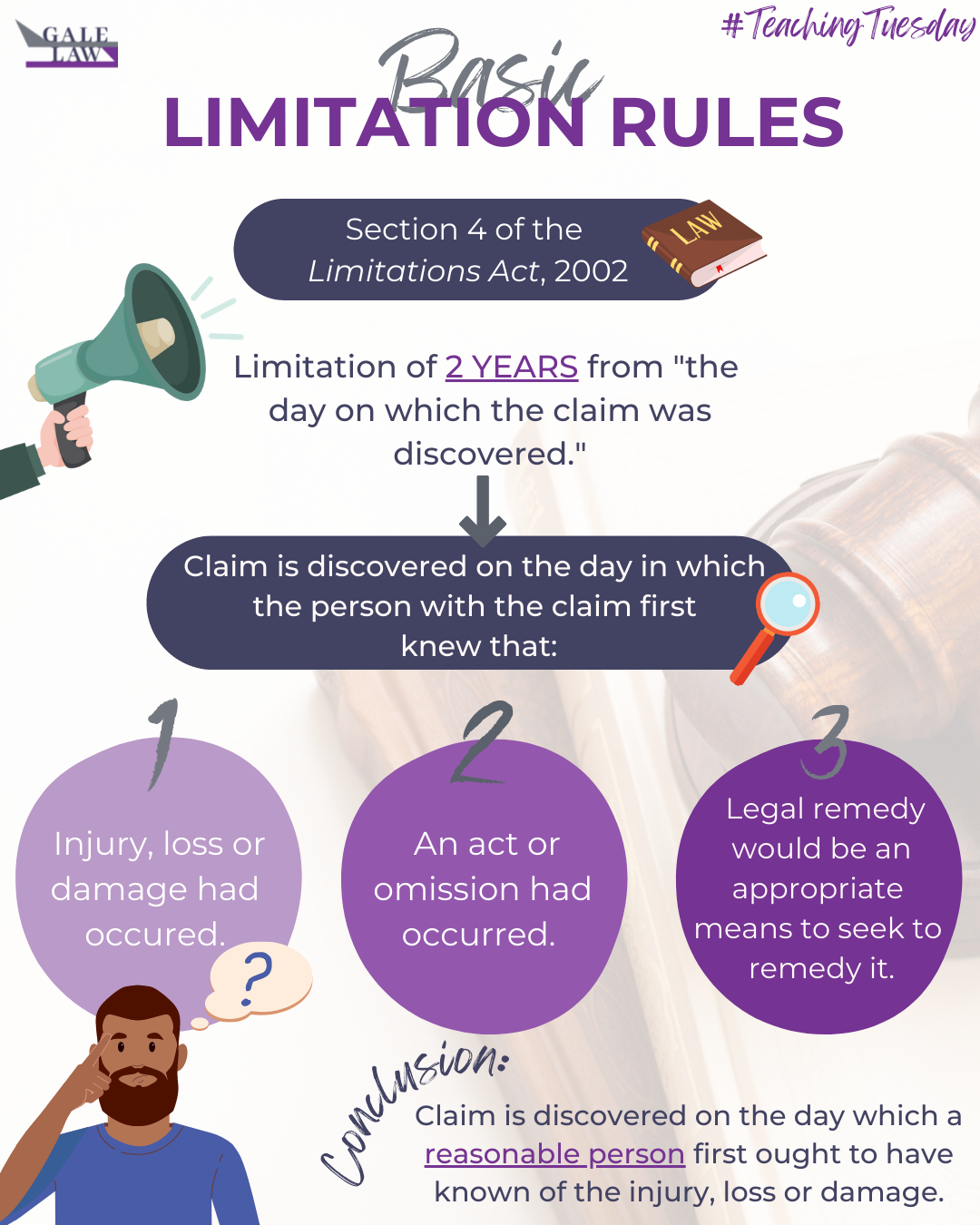

The Act states that the limitation period is two years from the date of the “discovery” of a claim. This two-year limitation period is termed as the “basic” limitation period.

In addition, there is an “ultimate” limitation period which is fifteen (15) years from the day of the act or omission.

Discoverability

Section 5 of the Act states that a claim is discovered on the earlier of:

(a) The day on which the person with the claim first knew the following:

(i) That the injury, loss or damage has occurred,

(ii) That the injury, loss or damage was caused by or contributed to by an act or omission,

(iii) That the act or the omission was that of the person against whom the claim is being raised,

(iv) That, having regard to the nature of the injury, loss or damage, a proceeding would be an appropriate means to seek to remedy it; and

(b) The day on which a reasonable person with the abilities and in the circumstances of the person with the claim first ought to have known of the matters referred to in clause (a).

The rule of thumb in estate litigation is that the claims must be brought within two years from the date of death (of the deceased’s estate that is the subject matter of the claim).

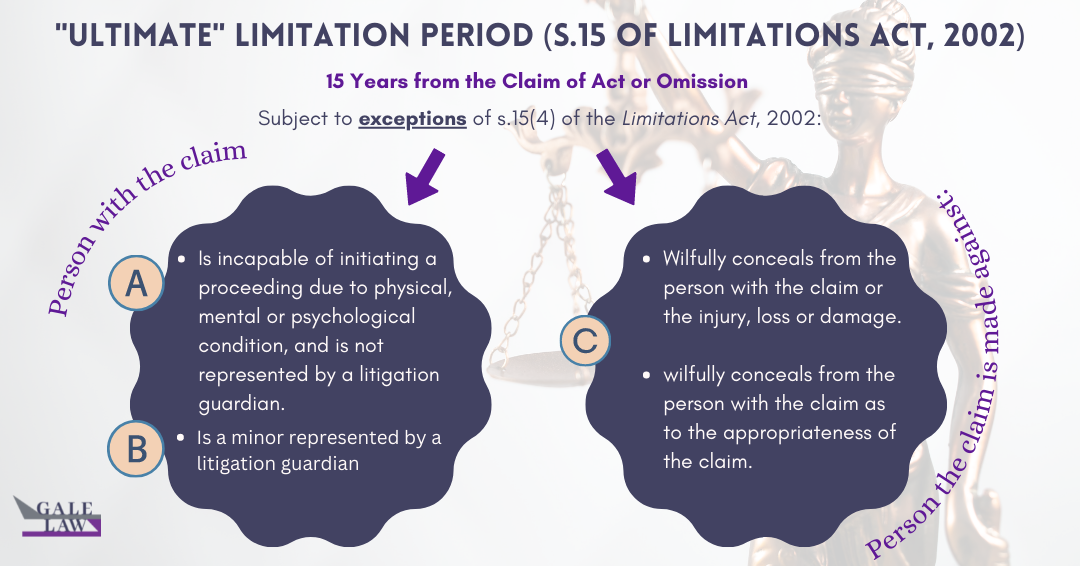

Ultimate limitation

In addition to the above basic limitation, Section 15 of the Act also prescribes an ultimate limitation period of fifteen (15) years. Subject to certain claims for which there is no set limitation period, the Act provides that irrespective of the discoverability of the claim, an ultimate limitation period of fifteen years is applicable.

The ultimate limitation is calculated from the day of the occurrence of the act or omission and not when the claim was discovered.

As the basic limitation of two years is included in the ultimate limitation of fifteen years, a claim cannot be made after the expiration of this fifteen years, even if it was not discovered within these fifteen years. It is imperative to clarify that the ultimate does not extend the basic limitation period. The ultimate limitation period cannot be used by parties to save already “dead claims.” The ultimate limitation period would not be applicable to claims that have already expired because they were discovered or discoverable more than two years before the proceeding commenced.

The Act makes it clear that in cases where an act or omission is continuous or prolongs, the limitation period would be calculated from the date on which the act or omission ceases to take place.

Exceptions to ultimate limitation

The exceptions provided in Section 15(4) of the Act can be summarised as follows:

The limitation period does not run during any time in which:

- The person with the claim is incapable of commencing a proceeding because of his/her physical, mental or psychological condition (s.15(4) (a) (i)), and

- Is not represented by a litigation guardian (s.15(4) (a) (ii))

- The person with the claim is a minor not represented by a litigation guardian (s.15(4)(b)),

- The person against whom the claim is made wilfully conceals from the person with the claim the fact that the injury, loss or damage has occurred, that it was caused by or contributed by an act or omission (s.15(4)(c)(i)), or

- Wilfully misleads the person with the claim as to the appropriateness of a proceeding as a means of remedying the injury loss or damage (s.15(4)(c)(i)).

Other Limitation Periods in Estates

It is relevant to mention that the Act applies to all claims, unless an express exception is set out. A limitation period in a statutory provision listed in the schedule will prevail over the limitation provisions of the Act.

Some of the other note-worthy limitations pertaining to estates litigation are as follows:

- Summary claims against the estate under Section 44(2), 45(2) and 47 of the Estates Act must be commenced 30 days after notice of contestation of claim.

- Court-directed distribution of estate assets under Section 17(3) of the Estates Administration Act R.S.O. 1990, c. E.22 must be commenced within 3 years from the court direction.

- Equalization claims under Section 7(3) of the Family Law Act must be commenced within 6 months after the first spouse’s death.

- Claim for support of dependants under Section 61 of the Succession Law Reform Act must be commenced within 6 months from the grant of a certificate of appointment.

- Personal claims under Section 38(3) of the Trustee Act must be commenced within 2 years from the date of death.

Conclusion

Counsel must be vigilant about the time for bringing claims. Counsel must ensure that the limitation doesn’t expire without them advising their client of its expiry or issuing a claim to preserve the limitation period.