Part 1: Duties of Estate Trustees and Lawyers in Administration of Estate:

Who Does What?

Co-authored by: Kim Gale and Palak Mahajan

Co-authored by: Kim Gale and Palak Mahajan

Co-written by: Kim Gale and Palak Mahajan

As we discussed in the first article in this two-part series, the decision of Alger v. Crumb, 2023 ONCA 209 (Alger), by the Ontario Court of Appeal addressed the issue of whether a general revocation clause in a will revokes designated beneficiaries.

In this case the court was faced with two issues:

On issue (a), the Court of Appeal observed that it is imperative to understand that a designation must specifically relate to a plan and a revocation must relate expressly to the designation. The court summarized the following propositions of interpretation:

The Succession Law Reform Act (SLRA) prescribes statutory requirements for the designation of a beneficiary by will and for the revocation of the designation by will, which varies from the requirements of revocation and designation by instrument. Specifically, a designation of a beneficiary by will relate expressly, whether generally or specifically, to the plan, while a revocation by will of the designation made by an instrument must relate specifically to the designation (s. 51(1) and s. 52(1) of SLRA).

Firstly, the court interpreted the general revocation clause to determine whether the designation is testamentary in nature. The answer is yes - the designations of beneficiaries by instruments of the RRIF and TFSA plans are testamentary dispositions.

Secondly, the court analyzed whether the revocation was made expressly.

The court noted the following:

At paragraph 25, the court states the following:

1) it must relate to the designation, as opposed to the plan; and 2) it must relate to the designation "expressly ... either generally or specifically".

At paragraph 25, the court states that the revocation must relate to the designation and not the plan. However, this stance is unclear as at paragraph 16 the court states:

Whereas s. 51(2) requires that a designation by will relate expressly to a plan, s. 52(1) requires that a revocation in a will relate expressly to the designation.

A bare reading of the remarks in paragraph 16 indicates that the revocation clause needs to mention both the designation and plan. However, paragraph 25 states that a revocation clause must include the designation and not the plan. This aspect of the judgment is ambiguous and needs clarification.

The Court of Appeal considered that "expressly" must mean something beyond a general category. Justice Kathryn Feldman referred to the thesaurus feature of Microsoft Word to support her conclusion and lay down the synonyms of "expressly." All the synonyms support the conclusion that reference to a general category that includes the thing to be referred to is not an express reference to that thing.

After due deliberation, it was held that as the general revocation clause in the testator's will does not relate expressly to the beneficiary designations made by the testator for her RRIF and TFSA plans, it does not comply with s. 52(1) of SLRA. As such, the general revocation clause was held to be not effective to revoke the designations of beneficiaries by instrument(s) of the RRIF and TFSA plans.

Issue (b): The second issue before Court of Appeal was whether the decision in Ashton Estate regarding the effectiveness of a general revocation clause in a will is correct.

The application judge chose to not rely upon the decision in Ashton Estate on the basis that the decision is "plainly wrong" (R v. Scarlett, 2013 ONSC 562, at para. 43).

The Court of Appeal in the decision of Alger held that court in Ashton Estate erred in finding that the clause in that case constituted an effective revocation of the earlier designation by instrument. It was observed that the application judge in Ashton Estate did not discuss the requirement that the revocation clause must relate expressly to the designation, whether generally or specifically.

Resultantly, the application judge in Alger was correct in finding that the interpretation of the general revocation clause in Ashton Estate should not be followed.

The Court of Appeal did, however, give a caveat that the result in Ashton Estate nevertheless appears to be correct under the provisions of SLRA, in the facts and circumstances of the case.

The decision in Alger has reaffirmed and reinstated the statutory requirements for designation and revocation by way of will and instrument. The judgment functions as a code to be followed in the contentious issues that might arise before the other courts from time to time.

This is the second in a two-part series. Read the first article: General revocation clauses and designated beneficiaries, part one.

This article was originally published by Law360 Canada part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.

Co-written by: Kim Gale and Palak Mahajan

The decision of Alger v. Crumb, 2023 ONCA 209 (Alger), by the Ontario Court of Appeal addressed the issue of whether a general revocation clause in a will revokes designated beneficiaries

A revocation clause is a clause in the will which expressly states that the will revokes any prior wills. It can be a simple one-line clause, such as, "I revoke all wills and codicils previously made by me." It is not required for a revocation clause to be included in a will; however, it is best practice to include this provision so there is no confusion if a prior will is still in force and effect.

A designation is a specific clause by which the testator/policy holder names someone to receive money, property, investments, or any other specific "benefit." There are certain assets whereby a named beneficiary can be nominated to receive the funds upon death of a person. Some examples of such instruments are life insurance plans, RRSPs/RRIFs and TFSA. The testator/ instrument holder can either name a beneficiary on the policy itself (in which case this is recommended and best practice to pass outside the estate and avoid probate tax). However, the testator/instrument holder may also name the beneficiary in their will.

In Ontario, designations are governed by section 51 and 52 of the Succession Law Reform Act, R.S.O. 1990, c S.26 (SLRA). Under s. 51(1), a participant can designate a beneficiary of a benefit payable under a plan on the participant's death through two mechanisms: (a) a signed instrument, or (b) by will.

A will is a legal document that is used to transfer holdings in an estate to other people or organizations after the death of the person who makes the will (the testator). An instrument is a testamentary document through which a specific plan/asset is designated to the nominees/beneficiaries specified in the instrument. These instruments can be life insurance plans, RRSPs/RRIFs and TFSA plans.

The Ontario Court of Appeal in the present case has clarified that the designations of beneficiaries by instrument(s) of the RRIF and TFSA plans are testamentary dispositions and therefore are included within the meaning of that term.

The decision of Alger is instrumental in interpreting the provisions of the SLRA that deal with designation and revocation by will and by instrument.

Section 51(1) of the SLRA states the following:

A participant may designate a person to receive a benefit payable under a plan on the participant's death.

Section 51(2) of the SLRA prescribes the following:

A designation in a will is effective only if it relates expressly to a plan, either generally or specifically.

Section 52(1) of the SLRA stipulates the following:

A revocation in a will is effective to revoke a designation made by instrument only if the revocation relates expressly to the designation, either generally or specifically.

Factual background

Theresa Lorraine Crumb (the testator) had four children, the appellants, and the respondents. By her will dated May 29, 2019, (the will), she named the appellants as her estate trustees.

The will leaves a $20,000 bequest to each of the respondents, some small bequests and the residue to only two of her children who are the appellants.

At her death, the testator had RRIF and TFSA plans at Scotiabank. By instrument(s) which were executed before the will, the testator designated all four of her children as equal beneficiaries of the plans.

The will contained a general revocation clause in paragraph one. In the affidavit, the appellants stated that the respondents were estranged from their mother during her final years and that was why she made her will to favour the appellants and that the general revocation clause was effective to revoke the designations.

The application judge found that because the general revocation clause did not relate expressly to the testator's existing designations by instrument(s) of her RRIF and TFSA plans, it was not effective to revoke those designations and the designations remained in effect.

Decision of application judge

The application judge made the following findings:

This is the first of a two-part series.

This article was originally published by Law360 Canada part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.

Co-written by: Kim Gale and Palak Mahajan

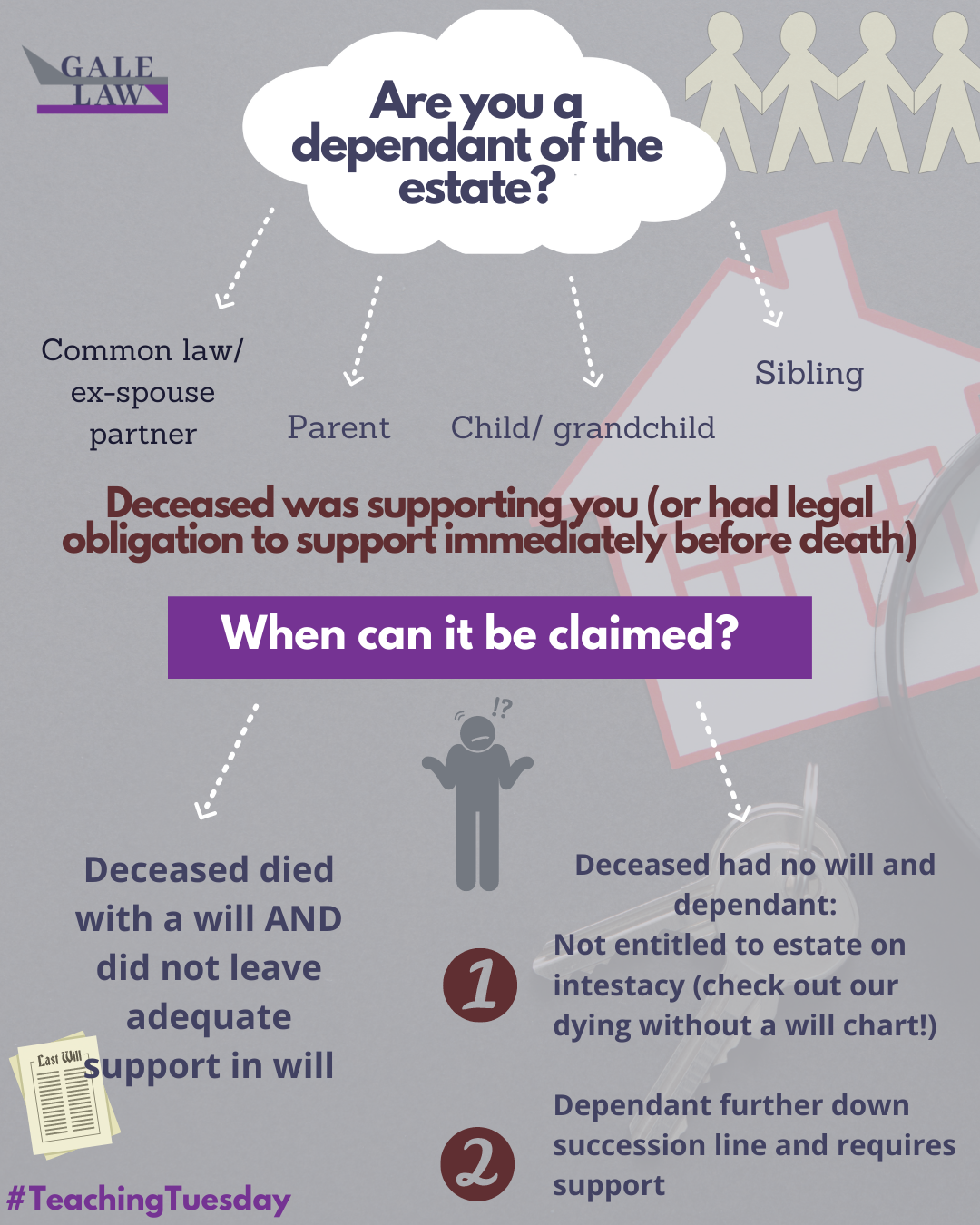

As a fiduciary for an estate, an estate trustee must comply with various legislation including the Succession Law Reform Act (SLRA) when disbursing estate assets and managing the estate. When dealing with a person who may be a dependant of the estate, and who may bring a Dependant Support Claim, estate trustees must adhere to s. 60 of the SLRA, failing which, they could be held personally liable. This article will consider the extent of an executor’s personal liability under s. 67(3) and remedies available to dependents should an executor disburse estate assets before a claim is heard.

What is a Dependant Support Claim?

A Dependant Support Claim is a claim initiated by an application against the estate of the deceased with whom the applicant is a legally recognized dependant of pursuant to s. 57 of the SLRA. A legally recognized dependant is defined as a spouse (common law or ex-spouse), parent, child/grandchild, or sibling of the deceased to whom the deceased was providing support to or was under a legal obligation to provide support to, immediately before their death. A Dependent Support Claim can be used in the following situations:

Limitation periods under SLRA: Six months

It’s important to remember that the general limitation period of two years does not apply to the timing of bringing a Dependant Support Claims.

Section 61 of the SLRA contains the limitation period. A claimant has six months from the granting of probate to bring a claim. The exception to this period is that a court may consider an application made at any time as to any portion of the estate which remains undistributed at the date of the application (61(1)).

An estate trustee must then comply with s. 67(1) which stays the distribution of the estate after service of notice upon them, until the court has disposed with the Dependant Support Application. The exception here is that an estate trustee may continue to make reasonable advances for support to dependants who are beneficiaries of the estate (67(2)).

Now, this is where things get interesting. Pursuant to s. 67(3), if an estate trustee distributes any portion of the estate in violation of ss. (1), and support is ordered by the court to be made out of the estate, the estate trustee is personally liable to pay the amount of the distribution.

Awareness of an impending claim can initiate personal liability

Executors can be held personally liable if they distribute the estate, to the dependant’s detriment, before the expiry of the six-month limitation period.

In Dentinger (Re), [1981] O.J. No. 303, the executors were aware that the dependant intended to make a claim under the SLRA, yet distributed nearly all of the estate’s assets shortly after probate and before the application was made. The executrices were advised within six weeks of probate being granted that the dependant intended to make a claim for relief under the SLRA. Within a further three weeks, the executrices rapidly conveyed all the real property in the estate to themselves and two other residuary beneficiaries. The Ontario Superior Court held the executors personally liable and ordered them to make a payment directly to the dependant.

Estate trustees can be held personally liable

Executors have a duty not to distribute the estate before the expiry of the limitation period if there is a possibility of a Dependant Support Claim, and if they do so, they do so at their own peril.

The leading authority on this issue is Gilles v. Althouse et al., [1976] 1 S.C.R. 353, where the Supreme Court of Canada considered Saskatchewan’s mirror legislation to the SLRA, The Dependants’ Relief Act of Saskatchewan. The estate had been fully distributed, and the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal had concluded for that reason that no order for maintenance could be made. The Supreme Court rejected the argument that executors were free to proceed with distribution until they had notice of an application for relief.

They unanimously found that at least until expiry of the six-month period, the applicant was a potential applicant under The Dependants’ Relief Act. She did not effectively disclaim any rights which she might have under that Act. The court opined that the true meaning and effect of the SLRA is to afford an applicant the opportunity to obtain an order against the entire estate, but if they delay and make an application after the six-month limitation period, the claim can only be against the portion of the estate which remains undistributed. However, if the executors have “distributed the estate in a manner contrary to the terms of the will as so varied, they will be under a duty to account.” (54).

The SLRA creates a “temporal window” which is commenced by the granting of probate. It is within this temporal window that the applicant must apply. Estate assets distributed after the temporal window has closed will not be subject to the applicant’s claim.

Should an executor distribute estate assets before a claim is heard, dependents may apply for relief through the clawback provision. Section 72 of the SLRA permits the court to “claw back” certain assets deemed to be part of the estate and subject to the application for support.

Non-arm’s length party can still incur personal liability

Executors will be held personally liable even if the estate trustee and dependant are non-arm’s length parties. In Gefen v. Gefen 2015 ONSC 7577, the estate trustee, the deceased’s spouse, distributed the estate to herself before the expiry of the six-month limitation period in the SLRA. The Superior Court found that the deceased’s son qualified as a dependant and was entitled to monthly payments. He was entitled to claim against the entirety of the estate as he brought his claim within the limitation period. However, the estate trustee had already distributed the estate assets. The court ruled that the estate trustee had distributed the estate at her own peril since she had not waited for the limitation period and that she was responsible for making the payments that otherwise would have been payable out of the estate itself, had she not made those distributions.

Responsibility for estate practitioners

Estate practitioners must be prudent in advising estate trustees of their personal liability in mishandling estate assets by distributing assets before the expiry of a limitation period. If an estate trustee has knowledge of a possible dependant and/or an impending Dependant Support Claim, they could be held personally liable to repay these funds in addition to other potential penalties if they distribute estate assets within the six-month limitation period following probate. They must also be aware that estate assets may be clawed back should a judge deem them to be a part of the estate.

This article was originally published by Law360 Canada part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.

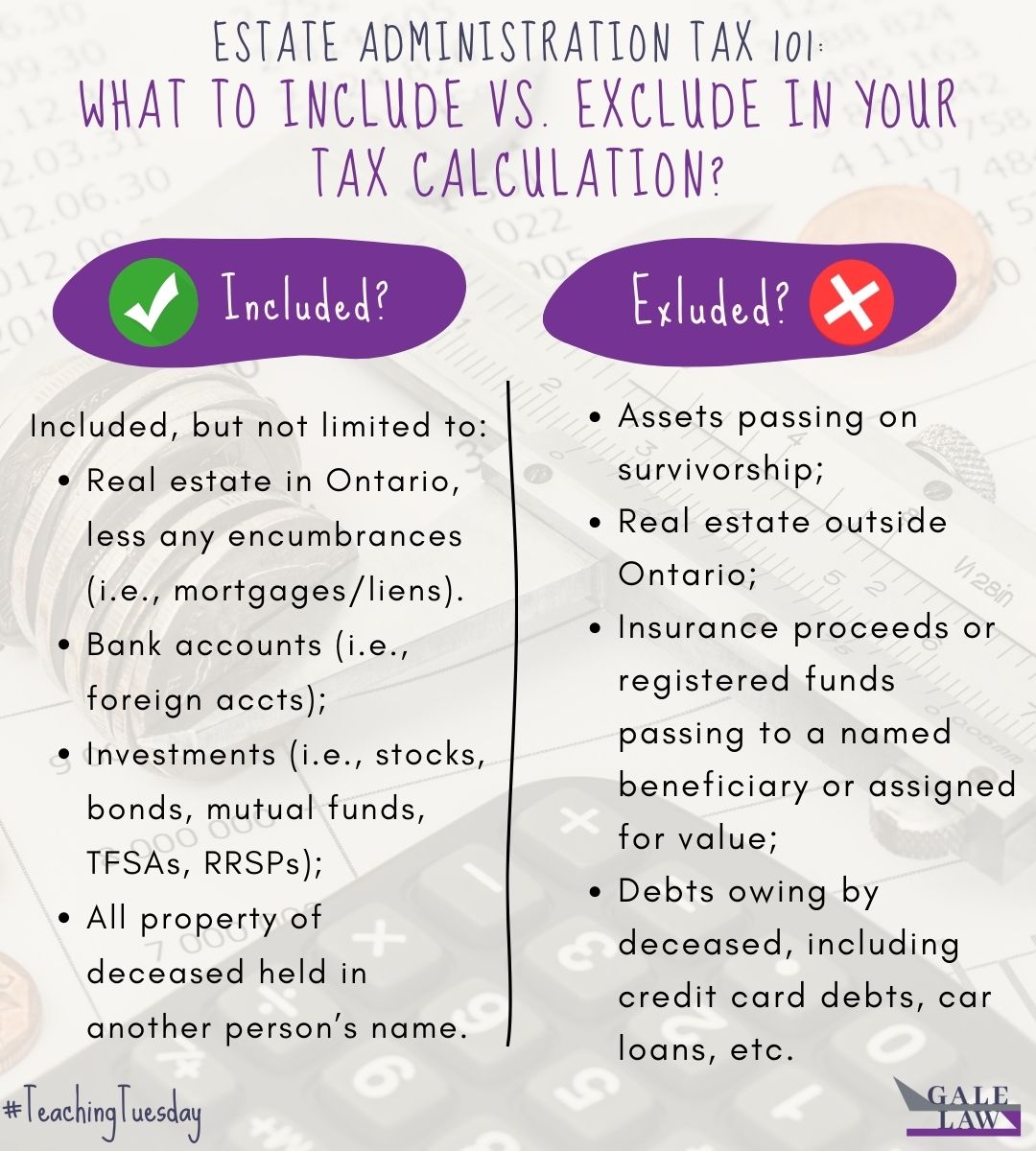

Tax planning in our daily lives can be frustrating, annoying and complicated. Tax planning for estates can feel even more onerous, complex and unimportant in our busy lives. With the emergence of COVID-19 however, estate planning has become more on the forefront of our minds. Understanding the tax implications of estate planning is pivotal to ensure that our loved one’s belongings are carefully considered and planned for.

In part one of this series, we will be providing the fundamentals of the estate administration tax.

Who applies?

The applicant is the executor or administrator of the deceased’s estate. The estate tax is a tax paid by the estate to “probate” a will, or in other words, to receive an order from the Superior Court of Justice granting an individual an estate certificate. This court order certifies and confirms that:

Who pays?

The estate tax is not paid from the estate representatives, but rather, from the accounts of the estate. The estate tax need not to be paid for the following certificates: Succeeding Estate Trustee with a Will, Succeeding Estate Trustee with a Will Limited to the Assets Referred to in the Will, Succeeding Estate Trustee Without a Will and Estate Trustee During Litigation.

How is it calculated?

As of Jan. 1, 2020, the estate tax is calculated as follows:

How is it paid?

The estate tax is paid in the form of a deposit and is calculated based on the value of the assets of the estate on the date of death. The value of the estate is all the property that belonged to the deceased person at the time of his or her death as explained below. Practitioners can also refer to s. 1(1) of the Estate Administration Act (Act).

So, which assets make up the value of the estate?

The following assets are included in the calculation of the estate tax:

All other property including goods, intangible property, business interests; and, Insurance if proceeds are left to the estate.

It excludes:

Exceptions to paying the estate tax

While the estate tax must be paid when the court issues an estate certificate, there are two exceptions to this rule:

While holding various types of assets can prove to be tricky in calculating the estate tax (even for estate lawyers) this helpful guide can serve as a starting point for estate representatives to consider which assets need to be ascertained, whether they need to pay the estate tax or not, and if they need to engage the services of an experienced estates lawyer. In part two of this series, we will move on to how to maximize tax savings.

As wills, trusts and estates practitioners, it is important to review the liabilities and entitlements of estate trustees on a regular basis to properly advise clients of what the role entails when they administer an estate. First, the liabilities:

General duties and responsibilities

The estate trustee should know that they have a fiduciary duty to administer the estate, meaning that the estate trustee must do their utmost to act in the best interest of the estate and follow the wishes of the deceased. The below list involves the general responsibilities that an estate trustee will usually face during the course of their administration:

Funeral arrangements: the estate trustee is generally responsible for the burial arrangement, with its costs, within reason, borne by the estate. The funeral expense is a proper expense to be reimbursed by the estate or paid for from the estate . An estate trustee should know that the burial instructions are not legally binding, and that the estate trustee has the authority to determine the specifics of the burial.

Locating the will and following the will (if any): the original will is necessary for probate with a will and for the estate trustee to act on behalf of the estate. The will is a living document and gives the estate trustee their power to act on the estate’s behalf. If there is no will, then an application for a Certificate of Appointment without a will is usually necessary.

Ascertaining the assets and liabilities: ascertaining the assets and liabilities is necessary to determine 1) the estate administration tax to be paid, and 2) how certain gifts (mainly in the residue) will be paid out. The estate trustee will need to determine if certain assets such as RRSPs, RRIFs, TFSAs and RESPs with a beneficiary designation, fall within the estate or pass outside of it. Once the assets are ascertained, the estate trustee will need to protect the assets to the best of their ability.

Applying for a Certificate of Appointment (if necessary): there is a need for the estate trustee to communicate with the beneficiaries of the estate to inform them of what they should expect to receive. These beneficiaries will have to be served with a notice of appointment. Usually, the estate trustee will need to open an estate bank account to administer the assets and liabilities of the estate. On almost all instances, the banks will require a Certificate of Appointment of Estate Trustee in order to open an estate bank account.

Paying taxes and debts: this includes providing a notice to creditors so that any creditors to the estate can submit claims before any debts or beneficiaries are paid. The estate trustee must also ensure that the taxes (including the income tax) and debts of the deceased are paid after the notice to creditors is advertised. The receipts will need to be kept for the accounting.

Passing accounts: the estate trustee must account for all the money that comes into and out of the estate for the beneficiaries. In this stage of the administration it is possible that the estate trustee can have the beneficiaries sign a release if they are satisfied with the accounting to release the estate trustee of their liability. If the beneficiaries do not sign a release, the estate trustee may wish to pass their accounts in court to be absolved of their liability. A passing of accounts may be necessary if the beneficiaries do not agree to pay the estate trustee his/her compensation.

Distributing assets according to the will: the estate trustee would have the responsibility to distribute the assets according to the will. Typically, the estate trustee is not expected to distribute within a year of the death of the deceased, called the Administrator’s Year.

What happens when estate trustee fails to perform duty or fulfil responsibilities?

A failure to perform the aforementioned duties and responsibilities may result in the following consequences:

Now we look at the entitlements:

Compensation

Generally, it is believed that the estate trustees can claim a five per cent compensation, but more accurately, it should be claimed based on the following percentages:

There are other factors in the common law that will determine the compensation an estate trustee may pay themselves. The leading case on this is the reference case of Re Toronto General Trusts Corporation and Central Ontario R.W. Co., [1905], 6 OWR 350. The factors that the court lists as important factors to be considered include:

Reimbursement

It is important for the lawyer to advise the estate trustee that the Trustee Act, RSO 1990 allows for estate trustees to reimburse themselves for their disbursements in the administration of the estate

Expenses of trustees

23.1(1) A trustee who is of the opinion that an expense would be properly incurred in carrying out the trust may,

a) pay the expense directly from the trust property; or

b) pay the expense personally and recover a corresponding amount from the trust property.

This reimbursement for estate trustees is supported by case law. In the 1802 English case of Worrall v Harford, (1802) 8 Ves 4, 32 ER 250, 34 ER 1002, Lord Eldon famously stated “It is in the nature of the office of trustee, whether expressed in the instrument or not, that the trust property shall reimburse him for all the charges and expenses incurred in the execution of the trust. That is implied in every such deed.”

In more “modern” times, Justice Ivan Rand (as he was then) in the 1945 Supreme Court of Canada case of Thompson v. Lamport, [1945] S.C.R. 343 ruled:

The general principle is undoubted that a trustee is entitled to indemnity for all costs and expenses properly incurred by him in the due administration of the trust: it is on that footing that the trust is accepted. These include solicitor and client costs in all proceedings in which some question or matter in the course of the administration is raised as to which the trustee has acted prudently and properly.

An estate trustee is entitled to indemnify themselves for all costs and expenses properly incurred by them in the administration of the estate.

The aforementioned duties, responsibilities, liabilities and entitlements is not an exhaustive list, but it is an informative starting point. Though there are numerous responsibilities that an estate trustee may assume, there are also many entitlements that can make the role rewarding. Perhaps the most rewarding benefit is ensuring that a loved one’s last wishes are carried out and their legacy is untarnished by conflict.

This article was originally published by The Lawyer’s Daily (www.thelawyersdaily.ca), part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.

On April 1, 2021, the estates law changes from the Smarter and Stronger Justice Act came into effect in Ontario. The result of the bill raised the limit for a small estate to $150,000 and introduced Rule 74.1 in the Rules of Civil Procedure pertaining to the administration of small estates.

This is similar to the increased limit in the Children’s Law Reform Act in instances where there is no Will or there is a Will but no trust provisions, the estate trustee can only pay $35,000 to the minors parent. Anything above that must be paid into court. The parent or guardian can then apply to be guardians of property their child. The amount was $10,000 previously.

As wills, trusts and estates practitioners it is important to note these changes to the legislation – in particular, estate administrators should be aware of the rules relating to small estates and how it affects the estates administration practice.

Small estates bond requirements

Pursuant to s. 35 of the Estates Act, there is a general requirement that requires every person to whom a grant of administration, including administration with the will annexed, shall give a bond to the judge of the court by which the grant is made. Generally, the administration bond that needs to be obtained is required to be double the amount of the assets of the estate. Pursuant to s. 36(3), an administration bond shall not be required in respect of a small estate, now up to $150,000 (unless a beneficiary is a minor or incapable).

Rule 74.1 small estates forms and procedures: What is the difference?

The major difference of Rule 74.1 is the probate process for small estates

The following demonstrates the requirements under Rule 74.04 in comparison to the requirements under Rule 74.1 (italic emphasis added):

Rule 74.04 Requirements for Probate Application

(g.1 ) Form 74.13.2 in the case of an application for a certificate of appointment of estate trustee with a will limited to the assets referred to in the will, a draft order granting the certificate of appointment;

Small Estates Rule 74.1.03 Requirements for Probate Application

Small estates have a less formal notice equivalent under Rule 74.1.03(3) that requires the applicant to send a copy of the application for a small estate certificate, any attachments and copies of the wills or codicils to the beneficiaries. It acts very similar to a Notice of Application for estates over $150,000.

As the highlighted passages above indicate, there are more requirements for probate under Rule 74.04 . There are up to six less forms required under Rule 74.1 and generally, there is no security required pursuant to s. 36 of the Estates Act, in comparison to a traditional Certificate of Appointment of Estate Trustee. Forms require time and time is money.

Comparison of forms

The small estate forms themselves are newer and easier for an administrator of a small estate to complete.

On an analysis of the Small Estate Certificate Form (Form 74. lA) in comparison to the Certificate of Appointment of Estate Trustee Form (Form 74.4) as downloaded from the Ontario Court forms website, at first glance, there are colour indicators in Form 74. lA that easily guide an administrator on where to fill in the forms as compared to the monochromatic Form 74.4. The spacing and larger text in Form 74. lA is placed in a way where it is more intuitive and user friendly than Form 74.4.

In terms of guiding language, the small estate form is clearer than its “traditional” counterpart, and as a snippet, the Personal Property section of Form 74. lA has a more in-depth definition of Personal Property as compared to Form 74.4 .

One interesting note from Form 74. lA, is that this form asks for the beneficiaries to be listed, whereas in 74.4, the beneficiaries are to be provided in another court form.

Who benefits?

According to Attorney General Doug Downey, raising the small estate limit was a part of the changes made “to ease the burden on grieving loved ones and ensure fairness for everyone regardless of the size of an estate, the government is making the process to claim a small estate faster, easier and less costly for Ontarians.”

Overall, the new changes make it easier for administrators of any estate under $150,000.

As some administrators may utilize legal counsel for the administration of their estate, having a process where there are potentially six less legal documents to complete, and a process that requires less correspondence with other parties will drastically help small estates by reducing time and legal fees paid from the small estates.

For the administrators who wish to administer a small estate by themselves, the new process is more simplified. Overall, it is faster, easier, and less costly in comparison to the process for estates over $150,000.

Do changes ensure fairness for everyone regardless of size of an estate?

For there to be winners, there must be losers borne from these changes . In terms of fairness for everyone, regardless of the size of the estate, it is puzzling how the line was arbitrarily drawn at $150,000.

What happens to the still relatively modest estates valued between $150,000 to $200,000? Should there be a system in place that is less onerous and less expensive than obtaining an administrative bond to compel an administrator to fulfil their duties?

The changes are a good start, but there are still questions that need to be answered.

This article was originally published by The Lawyer’s Daily (www.thelawyersdaily.ca), part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.

Estate COVID problems: The Rogue Trustee

A common theme in an administration of any estate is the breakdown of relationships between family members. Sometimes the estate trustee takes it upon themselves to make distributions that are not pursuant to the will or intestacy laws. It could be because they feel that they deserve more money over the other beneficiaries. Whatever the reason, an estate trustee should never endeavour to change the distribution as set out in a will or on intestacy laws without a court order.

Beneficiaries of a will or under intestacy who have not been given their inheritance because of an estate trustee’s conduct have recourse. This series of articles looks to address the problem: “I am a beneficiary of a will but I have not received my gift,” or “what do I do if the estate trustee is not distributing according to the will?”

No probate

If the beneficiary learns that they will not be receiving a gift before the estate trustee has applied for probate, then the beneficiary may file to the court a Rule 75.03 Notice of Objection to the estate trustee’s appointment. Essentially, the beneficiary would object to the estate trustee from obtaining the certificate of appointment because of the estate trustee’s conduct or conflict, which would interfere with them being able to act impartially among all beneficiaries (this is the even-hand rule).

The role of the estate trustee requires the trustee to serve the estate. If the estate trustee is unable to act neutrally and honour the last wishes of the deceased, or the laws of intestacy, then the beneficiary has a strong case to seek the removal of the estate trustee . Just because an estate trustee is a creditor does not mean they cannot act neutrally . Should an estate trustee be deemed by the court to have breached their fiduciary duties, they may be penalized with partially or fully reduced compensation, and in some instances forced to pay back the improper distributions to the estate with interest.

Duty to account

If the estate trustee has been appointed, either they obtained a Certificate of Appointment with or without a will, or were appointed in the will, then they have a duty to account to the beneficiaries. This means that the estate trustee must keep accurate records of the assets and transactions of the estate. The beneficiaries are entitled to see all the monies going in and out of the estate.

If the estate trustee is delaying distribution because they do not want to distribute to a beneficiary, or if they are not reporting anything to a beneficiary, or if a beneficiary suspects that they are not getting what they are owed, then the beneficiary can obtain an order to compel the estate trustee to pass their accounts (Rule 74. l S(h)) . If the beneficiary disagrees with the accounting, then they can file and serve a Notice of Objection to the Accounts (Rule 74.18(7)).

Other options include s. 37 of the Trustee Act, which states that a party may apply for an estate trustee to be removed or Rule 75 . 06 where the beneficiary may apply for the directions of the court.

The bottom line is if someone is a named beneficiary in a will or on intestacy, then they have the right to claim their inheritance.

What is different with COVID?

Luckily, the courts have adapted with the times and are hearing matters via Zoom. Law offices have transitioned to providing services to clients virtually. Though the medium is different, the law remains the law.

More on COVID-era estate law in part two of this series.