Tax planning in our daily lives can be frustrating, annoying and complicated. Tax planning for estates can feel even more onerous, complex and unimportant in our busy lives. With the emergence of COVID-19 however, estate planning has become more on the forefront of our minds. Understanding the tax implications of estate planning is pivotal to ensure that our loved one’s belongings are carefully considered and planned for.

In part one of this series, we will be providing the fundamentals of the estate administration tax.

Who applies?

The applicant is the executor or administrator of the deceased’s estate. The estate tax is a tax paid by the estate to “probate” a will, or in other words, to receive an order from the Superior Court of Justice granting an individual an estate certificate. This court order certifies and confirms that:

- the deceased’s will is valid, and;

- the applicant (either named in a will, or appointed without a will) has the legal authority to act as a representative.

Who pays?

The estate tax is not paid from the estate representatives, but rather, from the accounts of the estate. The estate tax need not to be paid for the following certificates: Succeeding Estate Trustee with a Will, Succeeding Estate Trustee with a Will Limited to the Assets Referred to in the Will, Succeeding Estate Trustee Without a Will and Estate Trustee During Litigation.

How is it calculated?

As of Jan. 1, 2020, the estate tax is calculated as follows:

- The first $50,000 of the estate or less is exempt from estate tax;

- Value exceeding $50,000: $15 per $1,000 (or any part thereof) for the estate value exceeding

- $50,000.

- Valuation of assets should be determined on the fair market value of the assets at the time of death. Estate representatives must be able to prove the value of assets through supporting documents (i.e., a statement of appraisal, financial statements, etc.). This can get quite complicated and may require the professional services of an appraiser.

How is it paid?

The estate tax is paid in the form of a deposit and is calculated based on the value of the assets of the estate on the date of death. The value of the estate is all the property that belonged to the deceased person at the time of his or her death as explained below. Practitioners can also refer to s. 1(1) of the Estate Administration Act (Act).

So, which assets make up the value of the estate?

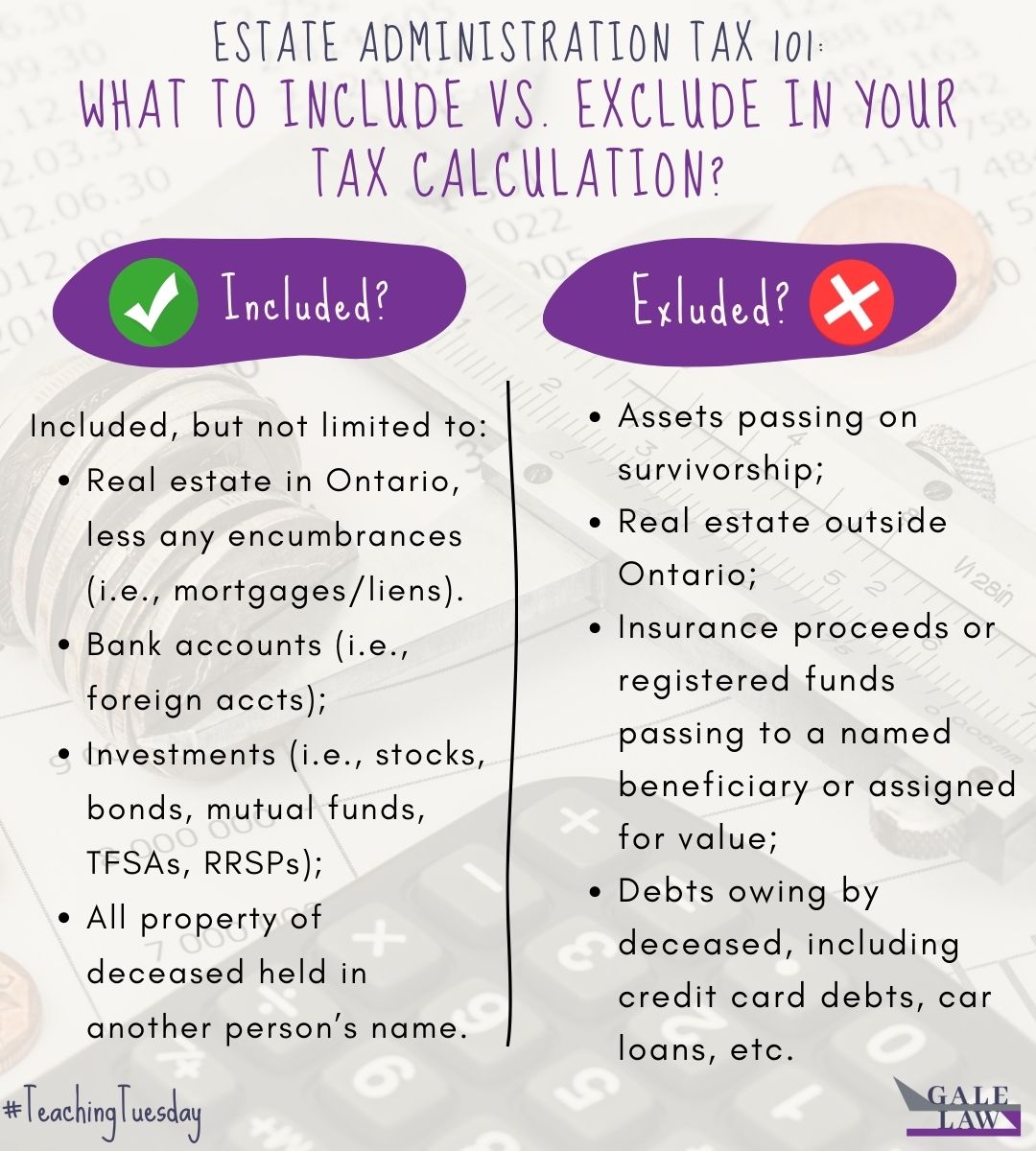

The following assets are included in the calculation of the estate tax:

- Real estate in Ontario, less the actual value of any encumbrance on real property (for example, mortgages and/or liens). The value used in this calculation is the appraised value at the date of death;

- Bank accounts (including foreign accounts);

- Investments (such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds, TFSAs, RRSPs); All property of the deceased held in another person’s name; Vehicles and vessels (for example cars, boats, ATVs, trailers, etc.);

All other property including goods, intangible property, business interests; and, Insurance if proceeds are left to the estate.

It excludes:

- Assets passing on survivorship;

- Real estate situated outside Ontario;

- Insurance proceeds or registered funds passing to a named beneficiary or assigned for value; and

- Debts owing by deceased, including credit card debts, car loans, etc.

Exceptions to paying the estate tax

While the estate tax must be paid when the court issues an estate certificate, there are two exceptions to this rule:

- The applicant must file an affidavit as to the estimated value, and the tax is based on the Additionally, the applicant must give an undertaking to file a sworn statement as to the value of the estate and to pay the tax within six months of that undertaking (Rule 74.13(2));

- If the court is satisfied, based upon the applicant’s affidavit and upon other material that the court requires:

-

-

- That the estate certificate is urgently required;

- That financial hardship would result from not issuing the estate certificate before the deposit is made; and

- That sufficient security for the payment of the estate administration tax has been furnished to the court.

-

While holding various types of assets can prove to be tricky in calculating the estate tax (even for estate lawyers) this helpful guide can serve as a starting point for estate representatives to consider which assets need to be ascertained, whether they need to pay the estate tax or not, and if they need to engage the services of an experienced estates lawyer. In part two of this series, we will move on to how to maximize tax savings.