Co-written by: Kim Gale and Palak Mahajan

Personal Liability of Estate Trustees in Dependant Support Claims

As a fiduciary for an estate, an estate trustee must comply with various legislation including the Succession Law Reform Act (SLRA) when disbursing estate assets and managing the estate. When dealing with a person who may be a dependant of the estate, and who may bring a Dependant Support Claim, estate trustees must adhere to s. 60 of the SLRA, failing which, they could be held personally liable. This article will consider the extent of an executor’s personal liability under s. 67(3) and remedies available to dependents should an executor disburse estate assets before a claim is heard.

What is a Dependant Support Claim?

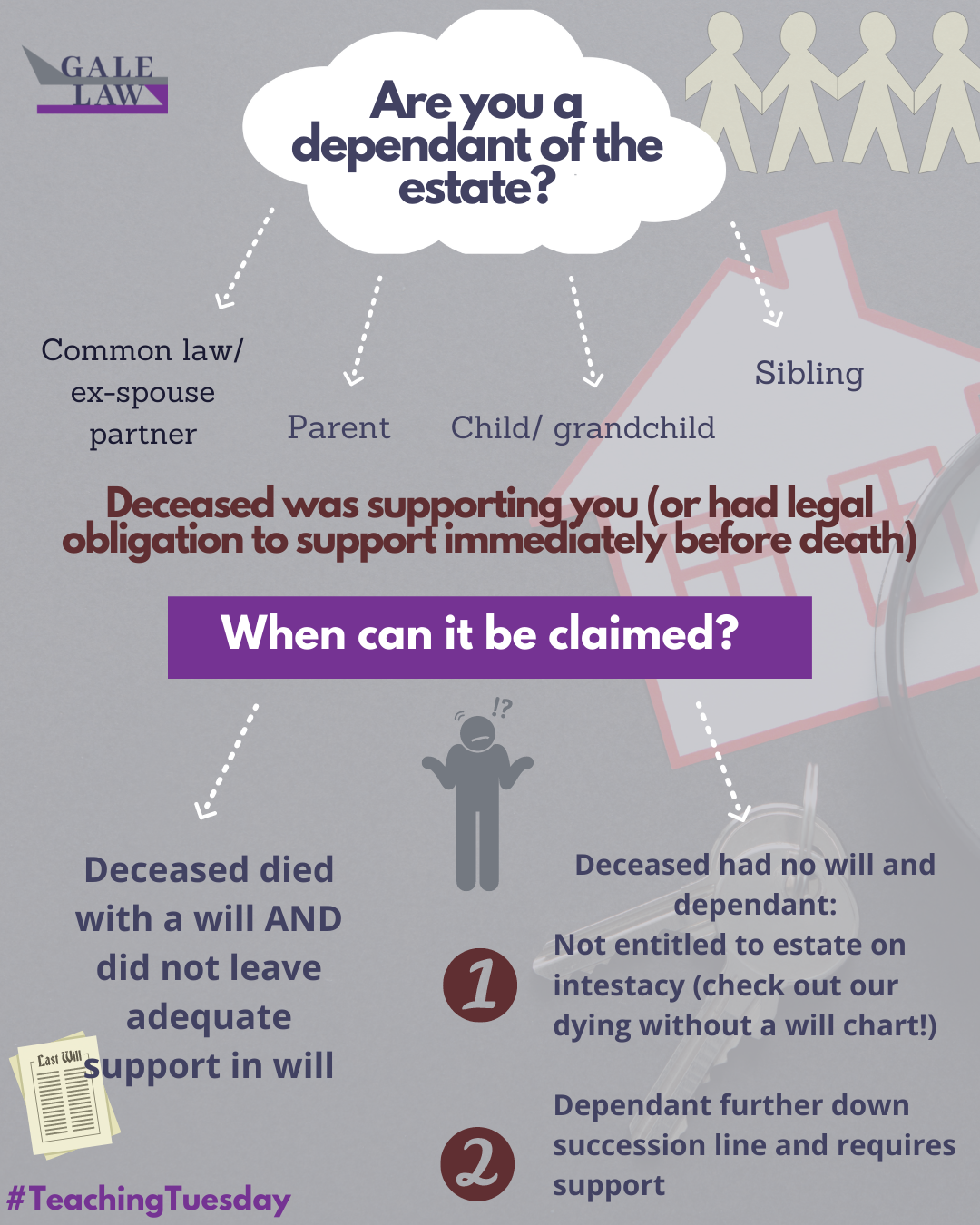

A Dependant Support Claim is a claim initiated by an application against the estate of the deceased with whom the applicant is a legally recognized dependant of pursuant to s. 57 of the SLRA. A legally recognized dependant is defined as a spouse (common law or ex-spouse), parent, child/grandchild, or sibling of the deceased to whom the deceased was providing support to or was under a legal obligation to provide support to, immediately before their death. A Dependent Support Claim can be used in the following situations:

- If the deceased died with a will and did not leave adequate support for the dependant; or,

- If the deceased died without a will and the dependent is: a) not entitled to relief from the laws of intestacy (i.e. common law spouses); b) the dependant is further down the line of succession and requires support from the estate.

Limitation periods under SLRA: Six months

It’s important to remember that the general limitation period of two years does not apply to the timing of bringing a Dependant Support Claims.

Section 61 of the SLRA contains the limitation period. A claimant has six months from the granting of probate to bring a claim. The exception to this period is that a court may consider an application made at any time as to any portion of the estate which remains undistributed at the date of the application (61(1)).

An estate trustee must then comply with s. 67(1) which stays the distribution of the estate after service of notice upon them, until the court has disposed with the Dependant Support Application. The exception here is that an estate trustee may continue to make reasonable advances for support to dependants who are beneficiaries of the estate (67(2)).

Now, this is where things get interesting. Pursuant to s. 67(3), if an estate trustee distributes any portion of the estate in violation of ss. (1), and support is ordered by the court to be made out of the estate, the estate trustee is personally liable to pay the amount of the distribution.

Awareness of an impending claim can initiate personal liability

Executors can be held personally liable if they distribute the estate, to the dependant’s detriment, before the expiry of the six-month limitation period.

In Dentinger (Re), [1981] O.J. No. 303, the executors were aware that the dependant intended to make a claim under the SLRA, yet distributed nearly all of the estate’s assets shortly after probate and before the application was made. The executrices were advised within six weeks of probate being granted that the dependant intended to make a claim for relief under the SLRA. Within a further three weeks, the executrices rapidly conveyed all the real property in the estate to themselves and two other residuary beneficiaries. The Ontario Superior Court held the executors personally liable and ordered them to make a payment directly to the dependant.

Estate trustees can be held personally liable

Executors have a duty not to distribute the estate before the expiry of the limitation period if there is a possibility of a Dependant Support Claim, and if they do so, they do so at their own peril.

The leading authority on this issue is Gilles v. Althouse et al., [1976] 1 S.C.R. 353, where the Supreme Court of Canada considered Saskatchewan’s mirror legislation to the SLRA, The Dependants’ Relief Act of Saskatchewan. The estate had been fully distributed, and the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal had concluded for that reason that no order for maintenance could be made. The Supreme Court rejected the argument that executors were free to proceed with distribution until they had notice of an application for relief.

They unanimously found that at least until expiry of the six-month period, the applicant was a potential applicant under The Dependants’ Relief Act. She did not effectively disclaim any rights which she might have under that Act. The court opined that the true meaning and effect of the SLRA is to afford an applicant the opportunity to obtain an order against the entire estate, but if they delay and make an application after the six-month limitation period, the claim can only be against the portion of the estate which remains undistributed. However, if the executors have “distributed the estate in a manner contrary to the terms of the will as so varied, they will be under a duty to account.” (54).

The SLRA creates a “temporal window” which is commenced by the granting of probate. It is within this temporal window that the applicant must apply. Estate assets distributed after the temporal window has closed will not be subject to the applicant’s claim.

Should an executor distribute estate assets before a claim is heard, dependents may apply for relief through the clawback provision. Section 72 of the SLRA permits the court to “claw back” certain assets deemed to be part of the estate and subject to the application for support.

Non-arm’s length party can still incur personal liability

Executors will be held personally liable even if the estate trustee and dependant are non-arm’s length parties. In Gefen v. Gefen 2015 ONSC 7577, the estate trustee, the deceased’s spouse, distributed the estate to herself before the expiry of the six-month limitation period in the SLRA. The Superior Court found that the deceased’s son qualified as a dependant and was entitled to monthly payments. He was entitled to claim against the entirety of the estate as he brought his claim within the limitation period. However, the estate trustee had already distributed the estate assets. The court ruled that the estate trustee had distributed the estate at her own peril since she had not waited for the limitation period and that she was responsible for making the payments that otherwise would have been payable out of the estate itself, had she not made those distributions.

Responsibility for estate practitioners

Estate practitioners must be prudent in advising estate trustees of their personal liability in mishandling estate assets by distributing assets before the expiry of a limitation period. If an estate trustee has knowledge of a possible dependant and/or an impending Dependant Support Claim, they could be held personally liable to repay these funds in addition to other potential penalties if they distribute estate assets within the six-month limitation period following probate. They must also be aware that estate assets may be clawed back should a judge deem them to be a part of the estate.

This article was originally published by Law360 Canada part of LexisNexis Canada Inc.